Financial engineering has witnessed a renaissance since we first published our whitepaper on the topic in January 2014. Given the national attention paid to US tax reform at the corporate and individual level, we thought an update would prove timely. The call for corporate tax simplification has been spurred not just by a desire to better align US rates and structures with global competitors, but in part as a response to some of the techniques described herein. Indeed the IRS has in recent years tightened the rules governing REITs and tax inversions and taken aim at §355 of the US tax code, the very underpinning for spin-offs.

Genuine tax reform could obviate certain financial engineering plays and lower rates could reduce its value, but we’ll take the under on when and how extensively tax change materializes. Whether we have already hit “peak financial engineering” because a new tax regime raises the hurdle rate for undertaking transactions or because the opportunities have been so well mined, there will always be a place for financial engineering to create and surface value in our view.

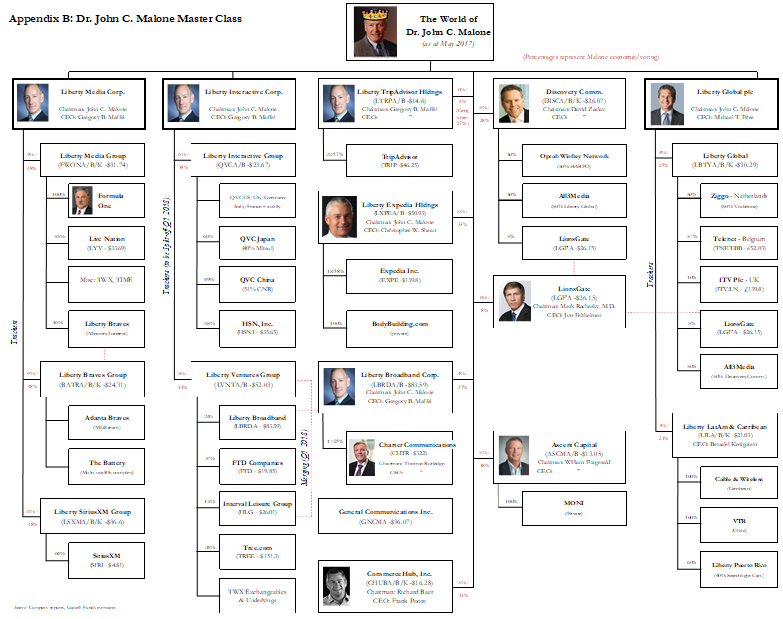

In addition to updating certain guidelines and exhibits, new topics in our 2017 Playbook include: inversions, yield companies, SPACs, and rights offerings. Of course, any survey of financial engineering must include an update on the gambits of the Grand Master of financial engineering, Dr. John C. Malone, included in Appendix B.

Financial engineering continues to be a natural focus for our firm since our Private Market Value with a Catalyst TM methodology, supported by deep, bottom-up research, predisposes us toward companies with underappreciated assets and managements focused on gaining recognition for those assets. The transactions described throughout this whitepaper have been, and should continue to be, rich veins for investment.

May 2017

Table of Contents

Preface ……..……………………………….…………………………………………………………

Introduction: Avenues for Value Creation/Surfacing ……………………………………

Financial Engineering Techniques

I. Reorganizations

A. Spin-Offs ………………………………………………………..….………………………

B. Exchange Offers/Split-Offs ………………………………..……….……….…………..

C. Cash Rich Split-Offs ………………………………………………………………………

D. Reverse Morris Trusts (RMTs) …………………………………….………..………….

E. Subsidiary IPOs …………………………………………………………………………..

F. Tracker Stocks …………………………………………………………………………….

II. Contingent Value Rights (CVRs)………………………………………………..……….

III. Inversions …………………………………………………………………………………….

IV. Capital Returns & Capital Raises

A. Share Repurchase ……………………………………………………..…………………

B. Dutch Tender ………………………………………………………………………………

C. Accelerated Share Repurchase ………….………………………………………………

D. Special Distribution …………………..………….………………………………………

E. Rights Offerings …………………………………………………………………………..

V. Public Pass/Pay-Throughs & YieldCos

A. Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) ………………………………………………

B. Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs) …………………………………………………

C. Yield Cos ………………………………………………………..………………………….

VI. Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) …………………….…………..

Appendix A: Selected Completed/Pending Spins …………….………………………..

” B: Dr. John Malone Master Class …………………….……..…………….….

Introduction: Avenues for Value Creation/Surfacing

We believe four primary levers lead to value creation/surfacing via financial engineering:

– Tax-efficient re-arrangement of assets for sale. The operations of diversified companies may appeal to different buyers. Rather than selling assets and potentially incurring corporate level tax, a number of companies (e.g. Fortune Brands, Cablevision, Sara Lee) have separated “wanted” from “unwanted” businesses via spin-off or exchange offer.

– Tyco stands out as a textbook example of the use of financial engineering to tax-efficiently disassemble a troubled conglomerate with excellent underlying assets. Through three sets of spin-offs, Tyco became six separate companies. Three companies (legacy Tyco, ADT, Covidien) were acquired, a fourth (legacy Flow Control, now Pentair) was the “buyer” in a Reverse Morris Trust transaction, leaving spin-offs Mallinckrodt and TE Connectivity still extant. Patient investors have been well-rewarded: from the time CEO Ed Breen began his turnaround in July 2002 to May 2017, a reconstituted Tyco would have compounded at over 16% vs the S&P 500 at 11%.

– Highlighting misunderstood dynamics. Corporations often possess businesses that diverge from their primary strategic thrust and thus are less well-followed. Separating those assets can force market participants to assign an appropriate value to those assets.

– Liberty Interactive, owner of multichannel commerce company QVC, issued a security known as Liberty Ventures (LVNTA) that tracks the value of an overlooked package of publicly-traded securities, cash and tax-advantaged liabilities. Since LVNTA began trading in August 2012 in a transaction that was also accompanied by a rights offering, it has risen from $45/share to a spin/split-off adjusted $75+/share as of this writing. Having established the market value of LVNTA’s assets, in April 2017 Liberty announced that it would legally separate the businesses through a merger and split-off.

– Improved capital structures. Returns to equity holders can be enhanced by reducing the cash flow shared with the government via taxes through the use of leverage or corporate structures such as REITs or MLPs.

– Gaylord Hotels owned and operated four large convention and lodging properties until selling its brands to Marriott Intl. and converting to a REIT (now known as Ryman Hospitality) in January 2013. In the process, it triggered a 240%+ rise in its adjusted share price from $19 in December 2011 to over $60 in May 2016.

– Focused management incentives. Sometimes called an “X-factor” and not mutually exclusive with any of the dynamics above, more closely aligning stock compensation with businesses managers actually control while giving talent the opportunity to excel in a public company environment often leads to better performance. We have observed that this is most often the case where the performance of one unit had previously been swamped by that of a much larger one (e.g. Madison Square Garden within Cablevision, Hertz Equipment Rental within Hertz).

Financial Engineering Techniques

In this section we review in greater depth the techniques and requirements of some of the most popular financial tools:

I. Reorganizations

A. Spin-offs. Under §355 of the US tax code, corporations may distribute assets to shareholders tax-free if they meet the following criteria:

(1) Control requirement: Parent must possess at least 80% of the vote of SpinCo prior to distribution.

Control Gathering Transactions

One method used to satisfy the control requirement has been the adoption of a dual-class structure in which the Parent issues “high-vote” shares to itself. In many cases, the structure would be immediately unwound. In 2016, however, the IRS eliminated such transitory structures, but offered two safe harbors: (a) no action is taken to unwind the structure for 24 months; or (b) SpinCo is acquired within 24 months provided there or no substantial negotiations regarding such acquisition.

(2) Active Business requirement: Parent and SpinCo must each actively conduct at least one trade or business after the distribution and have been conducting such trade or business for at least five years prior to the distribution (colloquially an “ATB”). Prior to 2016, no requirements existed for the size of this ATB (see below).

Buying an ATB

Given at least two ATBs are necessary for a spin-off, these entities can be valuable. Short of actually operating a business for five years, a company can only purchase an ATB in a transaction in which neither gain nor loss is recognized as Liberty Interactive attempted with its April 2017 purchase of General Communications.

(3) Device Test: The distribution must not be used principally to distribute the earnings and profits of a corporation.

Post-Spin M&A

The acquisition of Parent or SpinCo subsequent to a distribution will generally not fail the device test as long as there were no “substantial negotiations” – understood to mean the discussion of price – regarding a deal for two years prior to the distribution. Several safe harbors exist, including a waiting period of two years following a distribution. We note several acquisitions – including those of Ralcorp, Motorola Mobility, Orchard Supply and Remy International – were announced less than one year after their spin-offs, evidently because of an absence of substantial negotiations prior to the spin-off.

(4) Distribution requirement: Parent must distribute at a minimum “control” of SpinCo.

(5) Business Purpose requirement: The distribution must be motivated by one or more business purposes.

2016 Spin-Off Proposed Regulations

After a record year for spin-offs and in particular an attempt by Yahoo! to spin-off its then $30 billion stake in Alibaba using a business worth less than $200 million as an ATB, the IRS began evaluating ways to tighten the requirements of §355. In June 2016, it issued the following inter-related proposed regulations:

ATB Test

For the first time, the IRS has specified a minimum size for an ATB – 5% of total assets.

Device Test

The IRS begins its search for evidence of a device to distribute earnings and profits tax-free by measuring the ratio of a company’s Non-Business to Total Assets. Non-Business Assets would include assets not used in the conduct of the company’s business such as (a) “excess” cash; (b) partnerships owned <1/3rd; and (c) stock of third-parties where <50% of vote and value is owned. A high percentage of Non-Business Assets or a large difference in their ratios between Parent and SpinCo may be evidence of device.

The guidelines contain a safe harbor, not impacting transactions in which: (a) Non-Business Assets are <20% of Total Assets of Parent or SpinCo; or (b) the difference in the ratio of Non-Business to Total Assets for Parent and SpinCo is less than 10 pts.

In contrast, the guidelines also include a set of criteria in which a spin-off would be per se evidence of a device – i.e. the situations described in the table below are non-starters for tax-free treatment.

Situations not enumerated above would be judged on a case-by-case basis.

On April 21, 2017 President Trump signed an Executive Order instructing the Secretary of the Treasury to review all tax regulations issued since January 1, 2016. Thus, we may not have clarity on the status of §355 until late 2017 and ultimately the fate of these regulations may be determined in the context of larger tax reform.

Recognizing what may be a new reality, however, Yahoo! decided instead to sell its legacy assets in a taxable transaction, thus isolating its Alibaba and Yahoo! Japan stakes. More cleverly, Liberty Ventures, which had planned to spin-off of its stake in Expedia (clearly possessing high Non-Business Assets) with a modest-sized ATB, re-characterized the separation as a redemptive split-off (see page 9 for more), which are transactions not ordinarily subject to the device test. Although split-offs can bring added complexity, we see this route as an avenue that could be available to others.

Spin-Off aka “For Sale”

Corporations often run dual-track spin-off and sale processes with the announcement of a spin-off serving as a low-risk way in which to advertise a subsidiary for sale. This has been a popular tactic of late as illustrated below:

B. Split-offs (a/k/a Exchange Offers). Distributions that are not made pro-rata to all shareholders are known as “split-offs.” They are popularly employed as “exchange offers” in which shareholders can vary their ultimate holdings of Parent and SplitCo. As shown in Exhibit 3, a Parent company can choose to dispose of its stake in a subsidiary by offering shareowners the opportunity to volunteer to exchange their holdings of Parent for holdings of SplitCo at varying levels. The company selects a ratio of Parent to SplitCo (usually a discount to SplitCo’s ultimate trading price) that would clear the market and the Parent shares turned in by volunteering shareholders are retired.

Corporations can benefit from exchange offers (versus spin-offs) because they enable the shrinking of their shares outstanding. However, exchanges typically require a value for the SplitCo determined via a preceding IPO or by a “buyer” in a Reverse Morris Trust transaction. Shareholders more clearly benefit from exchanges because they allow the re-arrangement of holdings without having to incur the taxes and trading costs of buying one entity and selling the other.

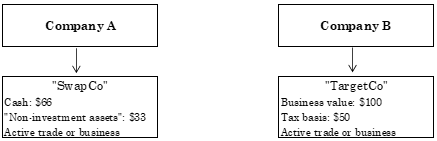

C. Cash Rich Split-Offs are a special class of exchange offers in which one party can tax-efficiently monetize appreciated assets.

Step 1: The “seller” of an appreciated stock (Company B) drops the appreciated asset into a subsidiary (TargetCo). To adhere to the requirements of §355. TargetCo must also include an “active trade or business.”

The “buyer” (Company A) creates a subsidiary (SwapCo) and places consideration consisting of no greater than 2/3rds cash, with the remaining consideration consisting of “non-investment assets” which may or may not serve as the ATB.

Step 2: Swap Co. and Target Co. are exchanged stock-for-stock and the subsidiaries are merged into their new parent companies tax free.

Cash rich splits are relatively rare because Company B, above, must hold and exchange shares in the “buyer” which, along with the other assets included, must be valued similarly by each party. In practice, buyers share in the tax savings of the seller by reducing the consideration paid for TargetCo in the example above.

As shown below, Warren Buffett utilized the strategy three times in two years; new rules governing the minimum size of an ATB may endanger its use in the future, however.

D. Reverse Morris Trust (RMT) is a transaction structure that allows corporations to simultaneously spin-off and merge a subsidiary with another entity tax-free. In an RMT, Parent spins-off its unwanted operation (SpinCo) to shareholders and simultaneously merges it with another company (MergedCo). The key requirement of an RMT is that former Parent shareholders must control 50% or more of the vote and value of MergedCo for some period after the transaction.

McKesson/CHC

In March 2017 McKesson announced an interesting twist on the RMT in which the merger takes place in private with an IPO and exchange offer following. In a set of initial steps, McKesson will contribute its digital assets to a newly formed LLC with Change Healthcare. McKesson will own 70% and Change, whose primary asset will be 30% of the JV, will go public as a company known as “Echo.” In a second step, McKesson will undertake a split-off in which certain of its holders will exchange their stock for shares of a NewCo which will immediately merge with Echo in a tax-free transaction.

E. Subsidiary IPOs (a/k/a Equity Carve-outs)can be used to highlight the value of ancillary businesses (Safeway/Blackhawk), raise capital for a parent (Cincinnati Bell/CyrusOne), the subsidiary or a minority investor (Expedia/Trivago), or arbitrage valuation differences between markets (Wynn Resorts/Wynn Macau). They are often followed by full spin-offs or exchange offers which can serve as a secondary catalyst for investors.

F. Tracker stocks divide the economics – but not legal ownership – of distinct businesses between different groups of shareholders. Parent and tracker companies share one Board of Directors, file one consolidated tax return and jointly retain liabilities in the case of liquidation.

Tracker stocks are used to attract shareholders of differing tastes and to highlight underappreciated assets where a spin-off may be sub-optimal because (a) tax assets are shared; (b) assets collateralize debt obligations; (c) flexibility to re-arrange assets is desired; or (d) the requirements of a spin-off (e.g. an ATB) cannot be met.

Tracker stocks were originated by General Motors after its purchase of EDS. In our view, tracker stocks have worked best when the tracked businesses are truly different and lack overhangs such as joint pension or other funding liabilities.

Note that over the next twelve months three tracker groups are likely to disappear: Fidelity National will spin-off Fidelity National Ventures; Liberty Interactive has announced a deal to split-off Liberty Ventures; and Liberty Global has made it known that it plans to spin-off LiLAC.

Trackers as Currency

A new use for trackers has been as acquisition currency. Before its acquisition by Dell in September 2016, EMC Technologies owned 80% of publicly-traded VM Ware. Dell Computer did not want to own – or at least pay for – EMC’s ownership in VM Ware and so issued a publicly-traded tracker stock to EMC holders reflecting ownership of VM Ware as part of the deal.

II. Contingent Value Rights (CVRs)

CVRs, typically issued as consideration in a merger, entitle the holder to additional value should certain contractual thresholds be achieved. CVRs are useful in bridging valuation gaps where the value of an asset cannot be agreed upon, often because it is reliant on the occurrence a binary event. Event-driven CVRs have been issued for: (a) sale of an asset; (b) settlement of litigation or regulatory action; (c) product (e.g. drug) approvals; or (e) post-closing financial adjustments. CVRs have also been used as a “true-up” or hedge to guarantee the seller a minimum price should the buyer’s currency deteriorate at a future time.

These securities are usually unregistered and non-transferrable. As a result they can be created at the time of the merger at significant discounts to their intrinsic value. In the select sample below we have highlighted non-biotech/pharma CVRs as they have been rarer; we estimate fourteen biotech/pharma CVRs have been issued since 2014 with seven having resulted in proceeds to date.

III. Inversions

In an attempt to escape relatively high US tax rates and a global tax system whereby profits earned in any jurisdiction are taxed when brought home, many US companies have domiciled outside the country via acquisition. To minimize further migration overseas, in August 2016 the IRS adopted §7874(a)2(b) which categorizes cross-border mergers into three buckets according to the pro forma ownership of US citizens:

As shown above, companies with domestic ownership greater than 80% remain US-domiciled while those with less than 60% domestic ownership are generally permitted to invert. In the latter case, the inclusion of 36-month look back for purposes of defining the amount of a NewCo held by US-domiciled investors was an attempt to prevent “creeping inversions” – where a non-US corporation executes a string of deals to bulk itself up in order to expropriate a US corporation – and “skinny down” transactions – where a US corporation makes itself smaller to keep US ownership of NewCo below the 60% threshold. This 36-month change effectively quashed the proposed merger of Pfizer and Allergan.

Like §355, these inversion guidelines are under review as a result of the President’s April 2017 order. Given the hostility the President has shown toward companies that re-domicile, we doubt there is much appetite to relax the inversion rules.

IV. Capital Returns

Companies return capital to shareholders in the form of dividends and share repurchases. Exhibit 10 includes twenty of the most aggressive repurchasers of stock – our Share Shrink Superstars. We have sorted the list by the reduction in actual shares outstanding over the prior five years in part to normalize for market capitalization and for option bleed. Our designation does not speak to the wisdom of each specific buyback. As a general rule, repurchases should only be conducted at a discount to intrinsic value and then only in cases where it is a company’s best risk-adjusted use of capital. We observe that a lack of capital alternatives may explain the predominance of retail, restaurant and “old” tech and media here.

There are some “special” cases of capital return we highlight:

A. Dutch tender. A Dutch tender offer operates like a reverse auction. A company offers to repurchase a specific number of shares within a given price range. Shareholders are invited to tender shares over a 20 day period, and do so by indicating the lowest price within the range that they will accept. The company aggregates investor offers, and buys the tendered shares up to the specified share limit at the lowest price possible. All shareholders who tendered shares at the accepted price or lower will have their tender offers accepted. If the company receives more offers at the accepted price than the specified share number, all shareholders receive a pro-rata allocation.

Ex: Dutch tender offer to repurchase 1,500,000 shares in the range $50-$53

Step 1: The issuer repurchases 1,500,000 at $52.50

Step 2: The issuer received 1,550,000 shares offered at $52.50 or lower

Step 3: Each investor who tendered at $52.50 or lower receives $52.50/share on a pro-rata allocation of 96.8% of tendered shares

The Dutch tender offer operates as an efficient clearing mechanism for large amounts of stock. Investors tend to want to receive the highest price possible, but risk being completely shut out of the offer if they tender their shares at the upper end of an offer. Issuers have the opportunity to amend the terms of the Dutch tender offer by changing the price range or increasing/decreasing the share amount, but doing so requires that the expiration of the offer period be extended by ten days.

B. Accelerated share repurchases (ASRs) are implemented through an intermediary which purchases the issuer’s stock in the open market over a specified time frame. Under an ASR, companies can reduce their weighted average share count instantly (increasing reported EPS), though they remain subject to transaction costs as the intermediary settles its outstanding share order.

C. Special dividend/distribution. In cases where small float and/or rich public market prices make share repurchase less attractive, companies have returned cash via one-time distributions. In some instances this can be tax efficient, as distributions are treated as a reduction in basis (rather than taxable income) to the extent that it exceeds a company’s accumulated earnings and profits.

Capital Raises

Once public, corporations can utilize a variety of structures to raise additional equity or quasi-equity including follow-on offerings, private investments in public equities (PIPEs) and convertible issuances. Each of these alternatives carries with it the potential for dilution to existing shareholders. Among the fairest and most efficient means of raising capital is the rights offering, a method more popular outside the US but successfully employed here by, among others, Liberty Media and closed-end mutual fund issuers such as Gabelli Funds.

D. Rights offerings. A corporation may distribute to existing shareholders the option or “right” to subscribe to shares of a new issue of common or preferred stock at a pre-determined price, typically at a discount to the market. Rights holders can choose to subscribe to the new issue or, if the rights are transferrable, sell them in the market.

If all existing holders fully subscribe to their rights, no dilution would occur since the company’s economic pie is sliced no differently. The ability to sell rights reduces the economic loss of a holder who does not exercise their rights since that holder would capture most of the spread between the rights offering price and the market value.

As shown above, if Company A’s stock is trading at $20 and it issues rights at $18, a holder of 10,000 shares should be able to sell their rights for their intrinsic value ($1.82/sh), resulting in $198,182 of stock and $1,818 of cash or $200,000 – a situation economically unchanged. Of course the real world entails friction costs (e.g. transaction expenses, spreads, stock prices that do not adjust precisely), but the result is almost certainly more favorable to existing holders than a straight equity offering. Most rights offerings also include the privilege to “oversubscribe” for additional discounted stock, shifting the pie in favor of alert/liquid investors.

V. Public Pass/Pay-throughs & Yield Cos

While most US public companies are ‘C’ corporations, the tax code grants special status to companies in certain industries. There are primarily two formats – Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) and Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs) – that can limit taxation at the corporate level.

A. REITs are real estate based businesses that distribute at least 90% of their pre-tax income (but unlike partnerships, not their losses) to shareholders as dividends. To qualify as a REIT, §856(c) of the tax code sets out the following qualifications:

– Income test: At least 95% of gross income from “passive” sources including dividends, interest and rents from real property. Further, at least 75% of gross income must be derived from “real estate” sources, primarily rents and mortgage interest.

– Asset test: At least 75% of assets must be in the form of real estate (including property and mortgages), cash or government securities.

Companies wishing to convert to REIT status must do so one year in advance and disgorge all “earnings and profits” in their first taxable years as a REIT. Income received for non-real estate services such as hotel management, may be derived from a Taxable REIT Subsidiary (TRS) owned by the REIT, but the aggregate size of a REIT’s TRS’ may be limited.

Over time the IRS had become more permissive about what constitutes rental income, clearing the way for prison, billboard, tower and fiber REITs. OpCo/PropCo structures, in which a company owning significant real estate (OpCo) would spin-off and lease-back those assets from a REIT (PropCo), also regained popularity. However, in December 2015, the IRS issued rules that prohibit companies involved in a spin-off transaction from converting to a REIT for a ten-year time frame, essentially ending that practice.

B. Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs) are passive investment vehicles exempt from paying entity level taxes if they meet two requirements:

– MLPs must be publicly traded.

– 90% or more of income must be from qualified income including interest, dividends and rent derived from the exploration, development, mining or production, processing, refining, transportation (including pipelines transporting gas, oil or products thereof), or the marketing of any mineral or natural resource (including fertilizer, geothermal energy, and timber).

Corporations can surface value by transferring qualifying assets into an MLP. This process, simplified in Exhibit 12 using a diversified utility that owns a pipeline, includes:

Step 1: Parent creates an MLP to hold 100% of the Pipeline

Step 2: MLP issues 65% economic interest (63% in the form of Limited Partner (LP) and 2% in the form of General Partner (GP) units) along with Incentive Distribution Rights (IDRs or performance fees) to Parent in exchange for Pipeline

Step 3: MLP IPOs 35% interest in the form of LP units and indirectly distributes the proceeds to Parent on a tax-free basis using a so-called “Lakehead structure”

MLP drop-downs can benefit Parent shareholders by reducing aggregate corporate tax paid, thus increasing the pool of distributable cash flow. A Parent may also arbitrage the valuation differences between MLPs and corporates through a drop-down. MLPs can themselves be attractive to unitholders because they allow tax deferral on a substantial portion (typically 80%) of annual distributions.

C. YieldCos are ‘C’ corporations or partnerships taxed as corporations that hold long-lived infrastructure assets with predictable cash flows that distribute 70-90% of cash flow to shareholders. The first YieldCos were created by utilities that sought a lower cost of capital (i.e. high multiple) for developed renewable assets that did not meet the qualifications to form an MLP.

The parent utilities often retain a controlling interest in the YieldCo, provide it with a long-term offtake agreement for power generation and continue to drop-down additional assets (classified as Right of First Offer assets) as they are developed.

YieldCos typically minimize cash taxes by utilizing an accelerated depreciation schedule for their assets. The need for continued access to depreciation shield and a desire to grow the dividend to increase the attractiveness of the equity necessitates the continued drop-down of assets.

VI. Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs)

Having appeared in other bull markets, SPACs have once again risen in prominence and gained institutional traction as a means for companies to go public. SPACs are essentially blind pools raised by a Sponsor to acquire a single unspecified target in a limited (typically two year) timeframe. There are three stages in the SPAC lifecycle:

A. Fundraising/IPO:

– Investors purchase $10.00 units = 1 common share + ½ warrant struck at $11.50/share

– $10.00 per share in cash is placed in a trust account; common and warrant are separated

– Sponsor funds offering and operating expenses (~3%) by buying Sponsor warrants

– Sponsor receives a promote = 20% of the equity, vesting on deal consummation

B. Search

– Sponsor has 18-24 months to secure an acquisition which cannot be known prior to IPO

C. Merger / “Second IPO”

– Sponsor negotiates terms of deal (typically short form merger) and conducts roadshow

– Investors may redeem their common for stated trust amount or continue as shareholders of “Newco.” Most merger agreements contain a maximum redemption threshold. Underwriters attempt match those who wish to redeem with investors seeking exposure to Newco, often sweetening participation with a sharing of the Sponsor promote.

Investors are enticed to purchase SPACs at IPO by the asymmetric risk/reward. If a SPAC fails to consummate a transaction or an investor chooses to redeem, they simply receive their $10.00 back, bearing only the opportunity cost of investing that $10.00 per share. In the meantime, the investor can separate and sell the warrant embedded in the unit which has option value even before a transaction is announced.

More broadly, the plusses and minuses of SPACs can be summed up as follows:

Competition for SPAC targets generally comes from the “regular way” IPO market and sales to strategic or financial sponsors. For a SPAC to successfully appeal to a target, they must solve some issue such as the lack of clean historical financials to go public (e.g. formerly bankrupt entities), the need for market sponsorship (e.g. for foreign entities), or a desire to immediately monetize some equity while retaining a stake in the upside (e.g. family companies with divergent interests).

The most appealing second IPOs tend to be those that create a public entity in an industry with a scarcity of publicly-traded assets and/or the ability to create a public traded entity at a demonstrable discount to public comps. In this way SPACs are relative trading vehicles usually requiring not only a robust equity market but a wide private-to-public multiple arbitrage that usually only exists late in the equity market cycle.

Exhibit 16 is a compilation of most major current generation (i.e. post 2010) SPACs that have consummated transactions. As illustrated, the track record for SPACs has been mixed but the quality of deals has been improving as more institutional investors (e.g. TPG, Gores) enter the market. Among the latest trends raising the profile of the SPAC vehicle has been sponsorship by retired “star” CEOs (e.g. Jim Kilts of Gillette, Mark Papa of EOG Resources) focused on making acquisitions within their core competencies.

Appendix A: Selected Completed/Pending Spin-Offs

Appendix B: Dr. John C. Malone Master Class

Why Profile Dr. Malone?

As should be evident from the exhibits above, the most active and proficient practitioner of financial engineering has been Dr. John Malone and his team (including Greg Maffei) at Liberty Media. Dr. Malone has had two successful runs at media moguldom. His first was building TCI into the world’s largest cable company before selling to AT&T in May 1999. The content and non-US cable assets gathered in the process of building TCI formed the basis for his current occupation at Liberty Media, a tracking stock of AT&T before its own split-off in August 2001.

Over the next fifteen years, Dr. Malone took Liberty Media – valued at the time of its split at $45 billion – and (a) leveraged and traded the assets to acquire meaningful positions in entities such as DIRECTV, SiriusXM, Charter Communications and Formula One; and (b) surfaced the value of other assets through nine spin/split-offs, three Reverse Morris Trusts, and six tracker stock issuances. This progression and the current state of the Malone empire are illustrated in exhibits below.

The two years since the publication of our first Financial Engineering Playbook have been especially active for Liberty. Undoubtedly the highlight was the closing of Charter’s acquisition of Time Warner Cable as time eventually “proved to be on their side.” Importantly, Liberty was able to put additional capital into US cable via Liberty Venture’s investment in Liberty Broadband. Other notable recent events included:

– Issuance of three tracker stocks (Liberty SiriusXM, Liberty Braves and Liberty Media) by Liberty Media Corp. (closing on tax day, April 15, 2016…)

– Spin/split-offs of CommerceHub and Liberty Expedia from Liberty Ventures

– Acquisition of Formula One by Liberty Media after a long pursuit

– Merger of Starz and LionsGate

– Formation of a Netherlands JV for Liberty Global’s cable and Vodafone’s wireless operations

– Announcement of separation of Liberty Interactive trackers into two asset-based securities through the acquisition of General Communications (to serve as an ATB), re-attribution of certain assets between the trackers and subsequent split-off.

Liberty shareholders have been well-rewarded by this flurry of activity as a purchase of Liberty in 2003, immediately before its first spin, has compounded at approximately 13.3% versus 7.5% for the S&P 500. Importantly, the secret to Liberty’s success goes beyond financial engineering – Dr. Malone has invested in good businesses at attractive prices and then recruited or retained high quality talent to operate them. Thus, financial engineering is but one of many tools that can be employed to enhance investment returns.

Appendix B: Dr. John C. Malone Master Class

Christopher J. Marangi

Mr. Marangi is Co-Chief Investment Officer, Value for GAMCO Asset Management (OTCQX: GAMI), and serves as Portfolio Manager of Value solutions. Christopher began his career at GAMCO as a research analyst covering the media industry sector, and later went on to lead the digital and media research team.

Mr. Marangi has appeared on CNBC, Fox Business and Bloomberg television and radio numerous times and has been quoted extensively in publications including the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Barrons, Newsday, Bloomberg, Variety and Broadcasting & Cable.

Mr. Marangi joined GAMCO in 2003 as a research analyst covering companies in the Cable, Satellite and Entertainment sectors. He began his career as an investment banking analyst with J. P. Morgan & Co and later joined private equity firm Wellspring Capital Management.

Mr. Marangi graduated magna cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa with a BA in Political Economy from Williams College and holds an MBA with honors from the Columbia Graduate School of Business.

Christopher J. Marangi (914) 921-5219 GAMCO Investors Inc. 2017

ONE CORPORATE CENTER RYE, NY 10580 GAMCO Investors Inc. TEL (914) 921-3700

This whitepaper was prepared by Portfolio Manager Christopher Marangi. The examples cited herein are based on public information and we make no representations regarding their accuracy or usefulness as precedent. The Portfolio Manager’s views are subject to change at any time based on market and other conditions. The information in this report represent the opinions of the individual Portfolio Manager as of the date hereof and is not intended to be a forecast of future events, a guarantee of future results, or investments advice. The views expressed may differ from other portfolio managers or of the Firm as a whole. Because the portfolio managers at GAMCO Investors, Inc. and its affiliates make independent investment decisions with respect to the client accounts that they manage, these accounts may have transactions inconsistent with the information contained in this report. These portfolio managers may know the substance of the report prior to its distribution.

This whitepaper is not an offer to sell any security nor is it a solicitation of an offer to buy any security.

Investors should consider the investment objectives, risks, sales charges and expense of the fund carefully before investing.

For more information, visit our website at: www.gabelli.com or call: 800-GABELLI

800-422-3554 • 914-921-5000 • Fax 914-921-5098 • info@gabelli.com